And in that sense, it would have been a fairly stable, habitable environment,” says Williford. “There’s water flowing in one side and out the other side, and so it would have been a dynamic system that survived for some significant amount of time. This makes Jezero what scientists call an open system. “One of the fantastic and fairly unique things about Jezero is not just that it was a crater lake, but that on the of that crater, there’s an outlet channel,” says deputy project scientist Ken Williford. Within Jezero, researchers have identified many appealing sites packed with minerals like clays, carbonates, and hydrated silica, which are of great interest due to their potential to preserve signatures of past life. Mission scientists selected Perseverance’s landing site, Jezero Crater, after whittling down about 60 initial options considered to be “astrobiologically relevant.” At 30 miles (49 kilometers) wide, Jezero Crater is an ancient lake and delta system located at the western edge of a giant impact basin called Isidis Planitia, just north of Mars’ equator.

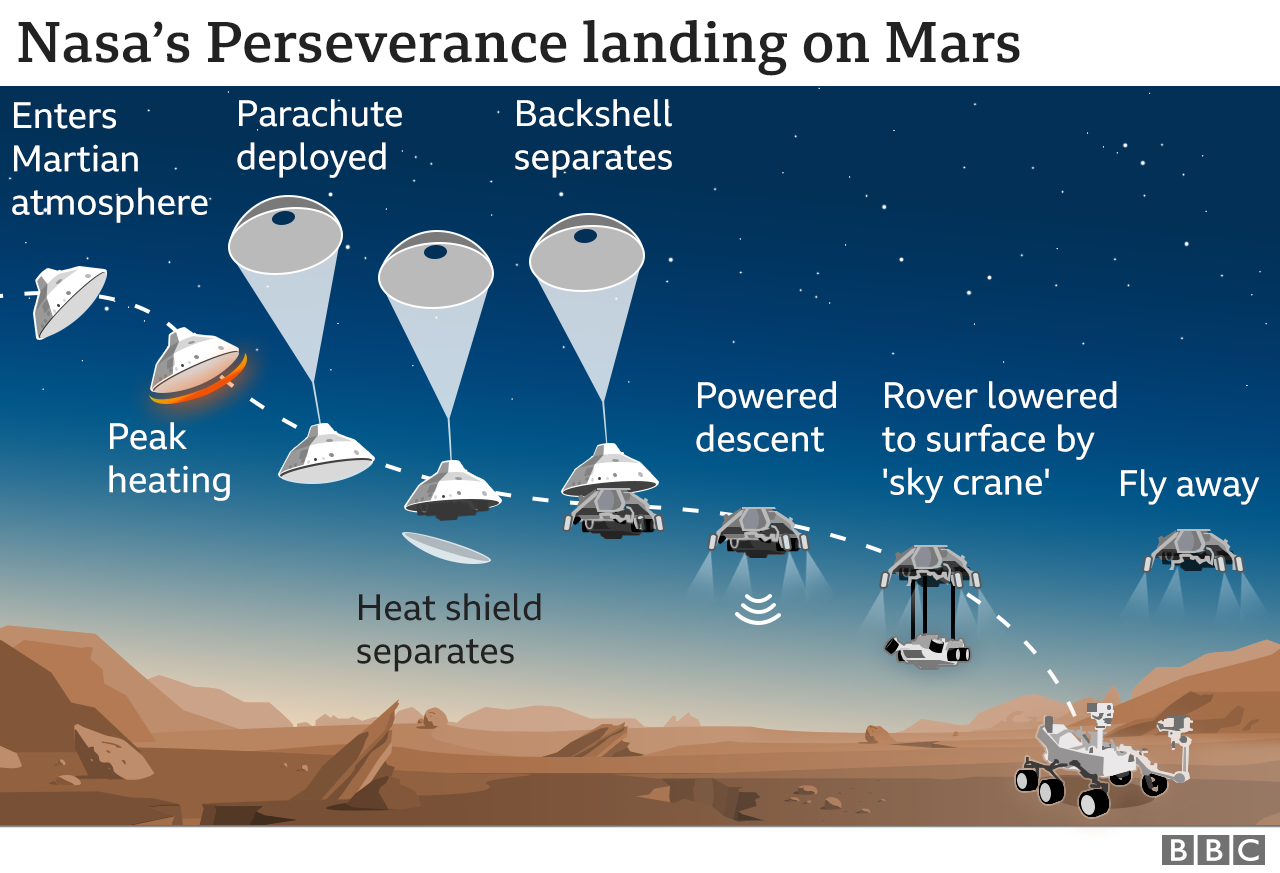

If the craft will fall short, it will hold off. But using Range Trigger, if onboard instruments determine Perseverance will overshoot its landing site, it will deploy its parachute early. Previously, parachutes were triggered as early as possible to ensure rovers didn’t smash into the ground. To help avoid such a long commute, Perseverance’s landing suite implements a Range Trigger strategy, which autonomously chooses when to deploy the craft’s parachute. But Perseverance also has a few new techniques that will further refine its ability to safely land at its intended dedestination: Jezero Crater.īecause rovers crawl, not zip, along the martian surface, if Perseverance misses its target, it could take weeks, months, or even a year to travel there, costing valuable mission time. Like Curiosity, Perseverance’s landing system relies on a parachute, a descent vehicle, and a nerve-wracking sky crane maneuver that lowers the rover to the ground like Tom Cruise dropping from the ceiling in Mission: Impossible. “That’s how they got the mission approved, because they could save an enormous amount of money by using those spare parts.” “ is something like 90 percent spare parts from Curiosity,” says Jim Bell, principal investigator for Perseverance’s Mastcam-Z instrument. For Perseverance, NASA is using what they call a “heritage approach,” borrowing what worked from Curiosity. That’s not due to laziness it’s part of the plan. Perseverance shares a lot with the Curiosity rover, and that’s because it uses the same basic design. Namely, the rover will seek signs of past life by searching for previously habitable sites search those sites for evidence of ancient microbes by studying rocks known to preserve life collect and store rock cores for a future sample return mission and help scientists prepare for the hurdles human explorers will face on Mars, partly by testing a method for pulling oxygen out of thin air.īut first, Perseverance must get to the Red Planet. There’s plenty of overlap between this mission’s goals and those of previous rovers, but Perseverance still has a unique agenda. And once engineers confirm it’s landed safe and sound, the rover will set to work achieving its four main objectives. Planned for launch between July 17 and August 5, the Perseverance rover will embark on a roughly seven-month journey to Mars, arriving February 18, 2021. Now, it seems that every time scientists make a new discovery about Mars, the conversation shifts to: “When are we going to go there and see for ourselves?” With this upcoming Mars mission, scientists are finally taking the first steps toward humanity exploring the Red Planet in person.

And they’ve found evidence that liquid water once existed on the now-arid planet, likely forming lakes and other bodies of water well suited for preserving ancient life - that is, if life ever existed there. They’ve uncovered reservoirs of water ice trapped at its poles and buried just below the ground. In recent decades, scientists have seen dust devils meandering along Mars’ barren surface. And though astronomers have mapped the planet’s surface from afar for hundreds of years, it wasn’t until the last half-century that we sent robotic scouts to physically explore and capture close-up views of the rusty world. Few worlds have garnered as much attention as Mars.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)